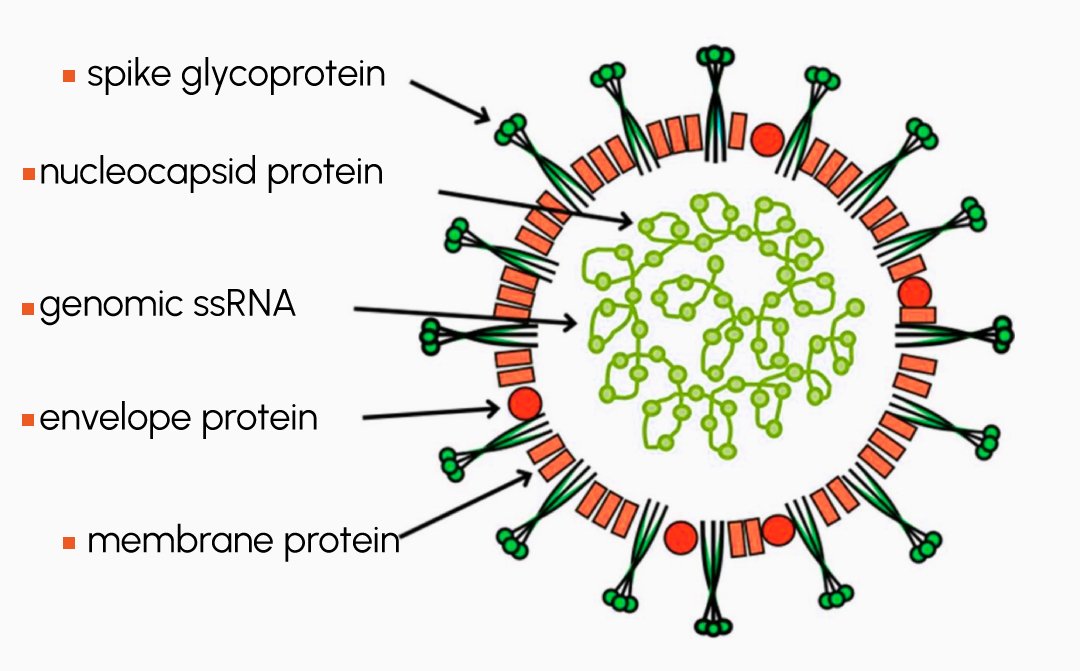

Feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) is the name given to a common and aberrant immune response to infection with feline coronavirus (FCoV). FIP is a viral disease that affects domestic and wild cats worldwide [1]. Recently, the virus, which has begun to spread rapidly in Southern Cyprus and has caused massive cat deaths, is likely to threaten cats around the world and create a new pandemic if not controlled.

FCoV, feline coronavirus, is a virus of the gastrointestinal tract that affects cats. The disease, FIP, develops when the mutated FCoV strain infects macrophages, a type of immune cell. The virus replicates within these cells, triggering an abnormal immune response that results in chronic inflammation and damage to various organs. FIP can affect multiple organ systems, including the liver, kidneys, lungs, and nervous system.

When a cat is exposed to the feline coronavirus, it can either eliminate the virus through its immune system or develop FIP. Most cats who are exposed to FCoV do not develop FIP, but in a small percentage of cases, the virus mutates and leads to the development of FIP. The factors that contribute to the development of FIP are not yet fully understood, but genetics, immune response, and environmental stressors are thought to play significant roles.

FIP can affect cats of all ages, but it is more commonly seen in young cats (under two years) and those with weakened immune systems. Crowded or stressful environments, such as multi-cat households, catteries, or shelters, may increase the risk of transmission and development of FIP. It is also believed that genetic factors have a role in the emergence of FIP. Male cats are more susceptible than female cats. FIP may be more likely to develop in pure-bred cats like Abyssinians, Bengals, Birmans, Himalayans, Ragdolls, and Devon Rex.

There is a lack of evidence that FIP is transmissible from cat to cat, although it may explain rare mini outbreaks of FIP [2]. A study on 59 FIP-infected cats found that unlike FCoV, feces from FIP-infected cats were not infectious to laboratory cats via the oronasal route [3]. FCoV is common in places where large groups of cats are housed together indoors (such as breeding catteries, animal shelters, etc.). The virus is shed in feces, and cats become infected by ingesting or inhaling the virus, usually by sharing cat litter trays or by the use of contaminated litter scoops or brushes, transmitting infected microscopic cat litter particles to uninfected kittens and cats [4]. FCoV can also be transmitted through different bodily fluids. The virus is easily spread through direct contact between cats. The most common form of spreading is through saliva, as most multiple-cat homes share food and water dishes [5]. Another major form of spreading is grooming or fighting. When an infected cat grooms a healthy cat, they leave their contaminated saliva on the fur. Later, when healthy cats go to groom themselves, they ingest the contaminated saliva and then become infected [6].

As mentioned above, there are two biotypes of Feline coronavirus: one type undergoes mutation, develops disease, and becomes fatal, while the other can be asymptomatic and can be eliminated without causing any fatal complications.

Feline Enteric Coronavirus (FECV) is the most common form of FCoV. FECV infects the lining of the intestines, leading to mild gastrointestinal symptoms such as diarrhea, vomiting, and occasional weight loss. Many cats infected with FECV show no clinical signs at all and can eliminate the virus from their system without complications.

In rare cases, FCoV can undergo a mutation, transforming into a pathogenic form known as the FIP virus. This mutated virus is responsible for the development of Feline Infectious Peritonitis (FIP), a severe and often fatal disease. The FIP virus can cause widespread systemic inflammation and affect various organs, leading to the characteristic symptoms and lesions associated with FIP.

It is crucial to understand that while FCoV infection is common, the development of FIP is considered a rare outcome. Most cats infected with FCoV will not develop FIP.

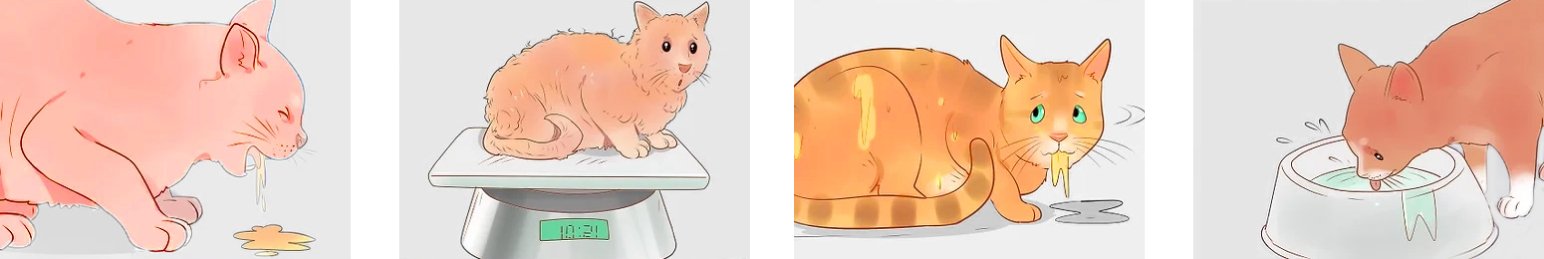

FIP can present in two major forms: effusive (wet) and non-effusive (dry). The wet form is characterized by the accumulation of fluid in body cavities such as the abdomen or chest, leading to distension and difficulty breathing. The dry form is more varied, affecting multiple organs and causing symptoms such as weight loss, lethargy, fever, neurological signs, and eye abnormalities.

Symptoms:

Symptoms of FIP can vary depending on the form of the disease. Common signs include weight loss, lethargy, fever, loss of appetite, jaundice, diarrhea, difficulty breathing, and neurologic abnormalities. These symptoms are nonspecific and can resemble other diseases, making diagnosis challenging

How to Diagnose Feline Infectious Peritonitis (FIP)?

Diagnosing Feline Infectious Peritonitis (FIP) can be challenging due to the lack of definitive tests. Veterinarians often rely on a combination of clinical signs, laboratory tests, and imaging studies to assess the likelihood of FIP. Here are some common diagnostic methods used:

- Medical History and Physical Examination:

The veterinarian will begin by gathering a detailed medical history of the cat, including any symptoms observed. A thorough physical examination will also be conducted to assess the overall condition of the cat and identify any abnormalities.

- Rapid Test Kits :

As there is no definitive test to diagnose FIP or distinguish FCoV from FIP, antibody detection is one of the most important tools for diagnosis. The VetFor FIP Rapid Antibody Test Kit is designed to help with this important diagnosis. The working mechanism of the kit is simply the qualitative detection of Feline Infectious Peritonitis Antibodies (Ab) in feline serum or plasma with a lateral flow sandwich assay.

- Blood Tests :

Bloodwork is an essential tool in diagnosing FIP. The veterinarian may perform a complete blood count (CBC) to check for changes in the white blood cell count and red blood cell parameters. An elevated globulin level, particularly the alpha-2 globulin fraction, may indicate FIP. Other abnormalities, such as anemia or changes in liver and kidney function, may also be observed.

- Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Testing :

PCR tests are used to detect the presence of the feline coronavirus (FCoV) or its mutations in the cat’s body. This test can be performed on various samples, such as blood, fluid from body cavities (effusions), or tissue samples. However, it is important to note that a positive PCR test for FCoV does not necessarily confirm FIP, as FCoV is common in healthy cats as well.

- Analysis of Fluid Samples :

In cases where effusions are present, the veterinarian may perform a procedure called abdominocentesis or thoracocentesis to collect fluid from the abdomen or chest, respectively. The fluid is then analyzed to assess its characteristics, including its protein levels, cell counts, and the presence of FCoV antibodies. High protein levels and the presence of certain cells in the fluid may indicate FIP.

- Imaging Studies :

X-rays and ultrasounds can help identify abnormalities in the organs and body cavities of a cat suspected to have FIP. These imaging studies can reveal fluid accumulation, enlarged organs, or granuloma formations, which are consistent with FIP. However, these findings are not specific to FIP and can be seen in other diseases as well.

It’s important to note that FIP diagnosis is often challenging and requires the veterinarian to consider multiple factors, including clinical signs, laboratory results, and imaging findings. Sometimes, a definitive diagnosis can only be made through a post-mortem examination (necropsy) of the cat.

If you suspect your cat may have FIP, it is crucial to consult with a veterinarian who can guide you through the diagnostic process and provide the best possible care for your feline companion.

Treatment of Fenile Infectious Peritonitis

Unfortunately, there is no known cure for FIP, and treatment options are primarily focused on supportive care to alleviate symptoms and improve the cat’s quality of life. Various experimental treatments, including antiviral drugs and immune modulators, have been explored, but their effectiveness remains uncertain. The prognosis for cats with FIP is generally poor, and the disease is often fatal.

Preventing FIP involves minimizing exposure to FCoV. Good hygiene practices, including regular cleaning and disinfection, can help reduce the spread of the virus. Reducing stress and overcrowding in multi-cat environments may also help decrease the likelihood of FCoV transmission. Vaccines are available for FCoV but have limitations in their effectiveness and are not considered fully protective against the development of FIP.

Since there is no cure for FIP, treatment focuses on supportive care to manage symptoms and improve the cat’s quality of life. Palliative measures may include medications to reduce inflammation, draining accumulated fluids, and maintaining hydration and nutrition.

- Palliative Care: The primary goal of treatment is to provide comfort and alleviate clinical signs. This may involve medications to reduce inflammation, such as corticosteroids, to help control symptoms and improve the cat’s well-being.

- Fluid Therapy: As FIP can cause fluid accumulation in the abdomen or chest (wet form), fluid therapy may be administered to relieve discomfort and maintain hydration.

- Nutritional Support: Ensuring proper nutrition is crucial. High-quality, easily digestible food or nutritional supplements may be recommended to maintain the cat’s body condition and support their immune system.

- Symptom-Specific Medications: Additional medications may be prescribed based on the specific symptoms present. For example, antibiotics may be given if secondary bacterial infections are suspected.

It’s important to note that the effectiveness of these treatments varies, and they are aimed at improving the cat’s quality of life rather than curing the disease.

It’s crucial to consult with a veterinarian if you suspect your cat is showing symptoms associated with FCoV infection or if you have concerns about their health. They can evaluate your cat’s condition, recommend appropriate treatment options, and provide guidance on preventive measures to minimize the spread of the virus.

REFERENCES

[1] Addie, D.; Belák, S.; Boucraut-Baralon, C.; Egberink, H.; Frymus, T.; Gruffydd-Jones, T.; Hartmann, K.; Hosie, M. J.; Lloret, A. (2009-07-11). “Feline infectious peritonitis. ABCD guidelines on prevention and management”. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 11 (7): 594–604. doi:10.1016/j.jfms.2009.05.008. PMC 7129471.

[2] Pedersen, Niels C. (2014). “An update on feline infectious peritonitis: Virology and immunopathogenesis.” The Veterinary Journal. 201 (2). Transmission of feline infectious peritonitis virus. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2014.04.017.

[3] Pedersen, Niels C.; Liu, Hongwei; Scarlett, Jennifer; Leutenegger, Christian M.; Golovko, Lyudmila; Kennedy, Heather; Kamal, Farina Mustaffa (2012). “Feline infectious peritonitis: Role of the feline coronavirus 3c gene in intestinal tropism and pathogenicity based upon isolates from resident and adopted shelter cats”. Virus Research. 165 (1). 4.2. Role of the 3c gene of FECVs and FIPVs in intestinal tropism and fecal shedding. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2011.12.020.

[4] [5] “Feline Infectious Peritonitis (FIP) Transmission – Feline Infectious Peritonitis (FIP).” HealthCommunities. Retrieved 2018-11-02.

[6] “FIP”. The Cat Community. Retrieved 2018-11-02.