Babesiosis is a tick-borne disease caused by protozoan parasites of the genus Babesia. The parasites invade red blood cells and can trigger hemolytic anemia and systemic illness. Dogs are diagnosed more often, but cats can also be affected, especially in tick-endemic areas. Because early signs are non-specific, risk awareness and timely testing are key.

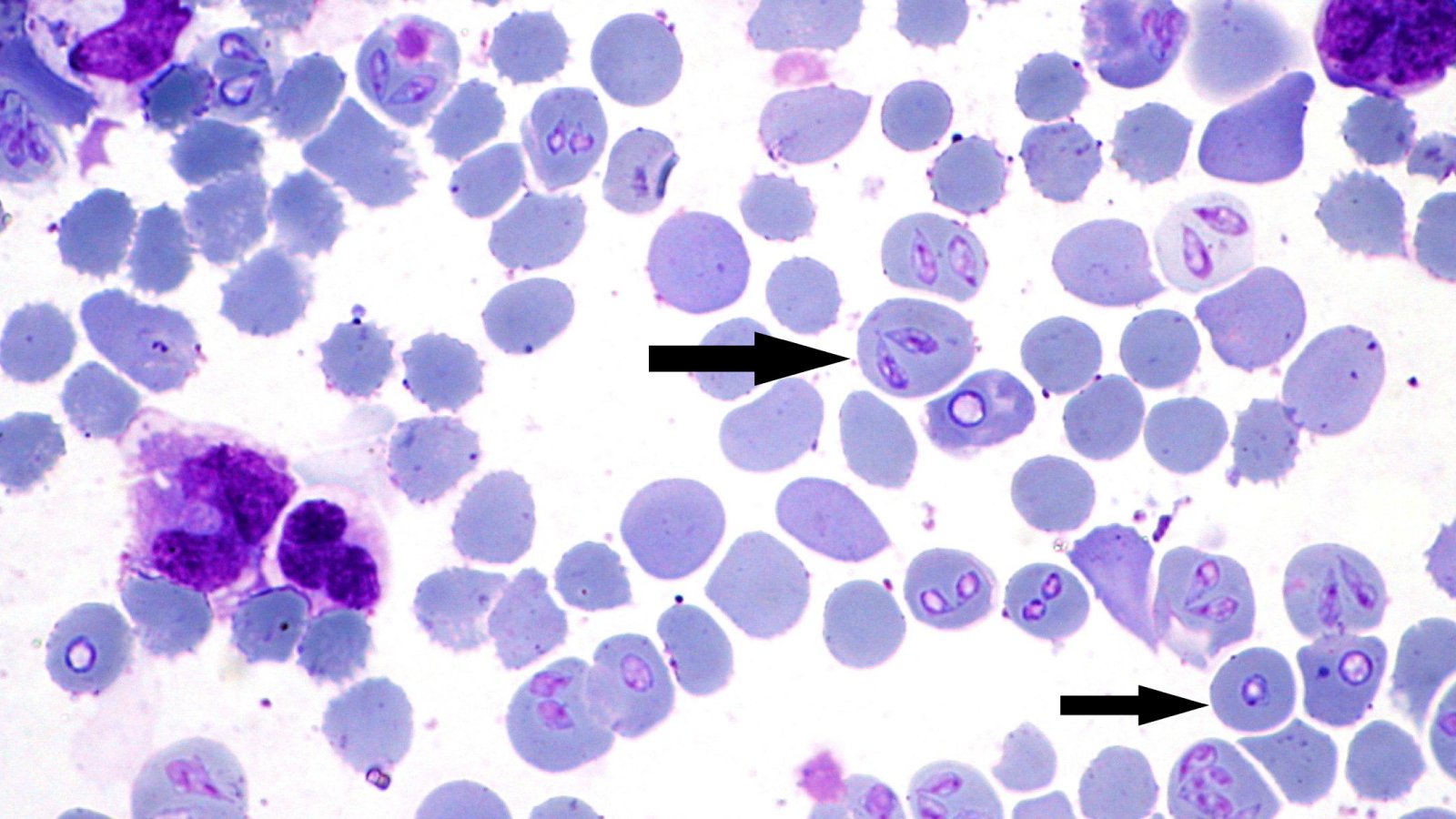

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Babesia-canis-dog.jpg

What is Babesia and why does it cause anemia?

Babesia lives inside red blood cells. As infected cells are damaged and cleared from the bloodstream, anemia can develop and organs may be stressed by inflammation and reduced oxygen delivery. In dogs, Babesia canis and Babesia gibsoni are among the most recognized causes. In cats, Babesia felis and other species have been reported, and cases may be missed when anemia is attributed to other conditions.

How do cats and dogs get infected?

Tick bites are the main route. Ticks transmit Babesia while feeding, so risk rises with outdoor exposure, contact with wildlife, and inadequate tick prevention. Dogs can also become infected through exposure to infected blood (for example, bite wounds, fighting, or unscreened blood transfusions). Some animals can remain carriers even after they look clinically well.

Clinical signs to watch for

Clinical signs can range from mild or even unnoticed to rapidly severe, but many are linked to anemia as red blood cells are damaged. Contact your veterinarian promptly if your pet shows lethargy, weakness, or reduced exercise tolerance, along with pale gums, rapid breathing, or a fast heart rate. Fever, decreased appetite, and weight loss may also occur, and some pets develop jaundice (yellowing of the gums or eyes) or pass dark, reddish-brown urine. In advanced cases, collapse can happen and should be treated as an emergency. Cats, in particular, may present with vague signs such as poor appetite, lethargy, a dull coat, and subtle weakness, so unexplained anemia in a cat or dog with tick exposure should raise suspicion for blood-borne parasites in the right clinical setting.

How veterinarians diagnose babesiosis

A physical exam and basic lab work (CBC and biochemistry) help assess anemia, platelet counts, and organ involvement. A blood smear can sometimes reveal parasites, especially in acute cases, but low parasite levels may be missed. PCR testing can detect Babesia DNA and may help identify the species, which can support treatment decisions and follow-up, particularly in endemic regions or in carrier animals.

Treatment and supportive care

Treatment depends on the Babesia species, disease severity, and the pet’s overall condition. Anti-protozoal medications may be used, and supportive care is often essential. Pets with significant anemia may need fluids, oxygen support, and sometimes blood transfusion. Because other tick-borne infections can occur in the same patient, veterinarians may also evaluate for additional agents when clinical signs and geography suggest risk. Even after improvement, follow-up testing may be recommended because some pets can remain carriers.

Prevention: the most effective approach

Prevention focuses on minimizing tick exposure, which is the most effective way to reduce babesiosis risk. Use veterinarian recommended tick preventives consistently and on schedule, and make a habit of checking your pet for ticks after outdoor activity so any ticks can be removed promptly. You can also lower the tick burden around your home by trimming grass, clearing brush, and limiting access to areas where ticks thrive. Because Babesia can also spread through infected blood, it is important to prevent dog fights and other situations that may involve bite wounds or blood contact. In veterinary settings, using screened blood donors is essential, and in endemic regions your veterinarian may recommend Babesia testing for at-risk animals, especially before blood donation or when exposure is suspected.

How VetFor supports Babesia testing

Early, accurate detection helps clinicians act faster. The VetFor animal health catalog lists a Babesia Detection Kit (VVC26) for canine and feline testing within its PCR product range, providing a molecular option that can complement microscopy and routine hematology when babesiosis is suspected.

This article is for educational purposes and is not a substitute for veterinary diagnosis or treatment.

References

MSD Veterinary Manual. Babesiosis in Animals.

MSD Veterinary Manual (Dog Owners). Blood Parasites of Dogs.

Companion Animal Parasite Council (CAPC). Babesia guidelines.

The Ohio State University and AKC Canine Health Foundation. Canine Babesiosis Fact Sheet (2023).

ABCD (European Advisory Board on Cat Diseases). Guideline for Babesiosis in Cats (updated, reviewed 2022).

VetFor Animal Health Catalog (PCR products list including Babesia Detection Kit VVC26).